The Bengal Florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis), one of the world’s most elusive bustard species, teeters on the brink of extinction with fewer than 1,000 mature individuals left globally. This critically endangered bird exists in two fragmented populations: Houbaropsis bengalensis blandini in Cambodia and Houbaropsis bengalensis bengalensis in India and Nepal. Sadly, it has already vanished from Bangladesh and Vietnam. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the Bengal Florican as critically endangered, underscoring the urgency for comprehensive conservation measures. In Nepal, it is one of the nine protected species under theNational Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2029 (1973), and its inclusion in CITES Appendix

Historically, the Bengal Florican was widespread across the Terai’s lowland grasslands.However, habitat loss due to agricultural expansion, human settlements, and natural succession has drastically curtailed its range. Today, its breeding distribution has been confined to a few protected grassland areas. While, the farmlands provide refuge during the non-breeding season.

Nepal harbors fewer than 100 Bengal Floricans, with recent surveys suggesting a sharp decline to fewer than 50 individuals. These birds have been found to primarily inhabit in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, Shuklaphanta National Park, and Chitwan National Park. They have not been found to be sighted in Bardiya National Park since 2012. As a solitary and territorial bird, the

Bengal Florican is a habitat specialist, thriving in open, short, alluvial grasslands with scattered bushes. The ongoing degradation of Terai grasslands, both within and outside protected areas, poses a severe threat to their survival.

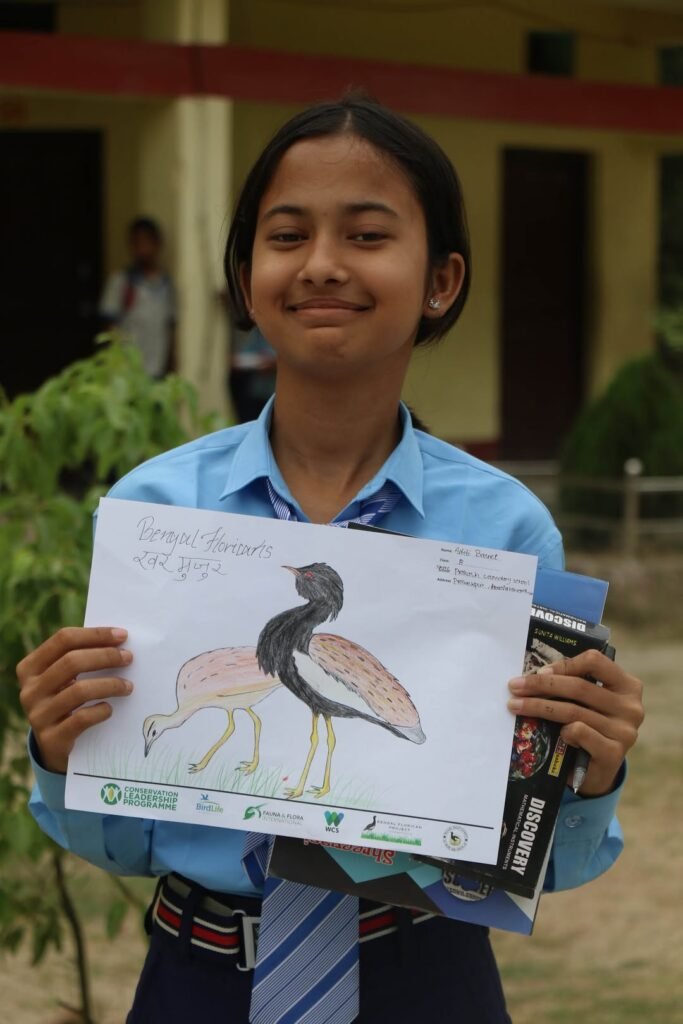

Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, a stronghold for the species, supports Nepal’s smallest Bengal Florican population. However, overgrazing and disturbances from people and cattle, particularly during the breeding season, are major threats in this region. Supported by the Conservation Leadership Program (CLP), my team and I conducted extensive surveys to better understand and protect this rare bird. The Bengal Florican is notoriously shy, hiding in the grass at the slightest disturbance. Males are strikingly black and white, while females are larger and light brown, blending seamlessly into the dry grasslands they prefer. During the breeding season, males perform elaborate displays, puffing their neck and chest feathers and strutting around to attract females. These courtship rituals are a vital part of their reproduction strategy yet remain poorly documented and warrant further research.

Bengal Floricans prefer tall grass and depressed lands for hiding. They blend into their surroundings so well that they become nearly invisible. The bird is most active during dawn and dusk, foraging on a diet of insects like grasshoppers, beetles, ants, and occasionally small reptiles and snakes. They also consume grass, flowers, shoots, berries, and seeds. However, survival of this species has been threatened by several factors. Our surveys frequently observed Bengal Floricans foraging alongside feral cattle in Koshi Tappu, raising concerns about the impact of livestock on their habitat. As they are ground-nesting birds, their eggs have been found to vulnerable to trampling by animals and disturbance by humans.

Local communities in Koshi Tappu heavily depend on the reserve for resources like fish, fodder, and seasonal vegetables. During our research, we documented various traditional fishing methods and the collection of Ningbo, an edible fern, from the reserve. The tall ‘khar’ grass, essential for thatching roofs, has also been found to be harvested here. The Bengal Florican favors open, short grasslands for establishing territories, often within expanses of taller grasses and scattered bushes. Short grasslands are ideal for foraging and displaying, whereas, the birds seek shelter in taller grasses during the heat of the day. Females spend much of their time in these tall grasses during the breeding season, which starts in late March and lasts until early July.

During this period, males become highly territorial and perform aerial displays, making their white wings conspicuous as they fly in circles with shallow, rapid wingbeats.The effects of grazing on the grassland ecology has not been understood clearly yet. But, some level of cattle grazing may benefit the Bengal Florican. This requires further research.Meanwhile, locals in Koshi Tappu continue to rely on the reserve and its buffer zones for essential resources, leading to untimely, accidental, and repeated fire incidents during the breeding season. Additionally, invasive species like Mikania micrantha degrade the grasslands, while an increase in predators such as the Asiatic golden jackal, Indian grey mongoose, and feral dogs poses further threats.

Conservation efforts must be significantly intensified to ensure that the future generations can witness the Bengal Florican in the wild. Detailed research and active community involvement are crucial to developing and implementing effective strategies for the bird’s protection in Nepal’s lowlands. The Bengal Florican’s survival depends on our collective commitment to preserving its habitat and addressing the myriad threats it faces.